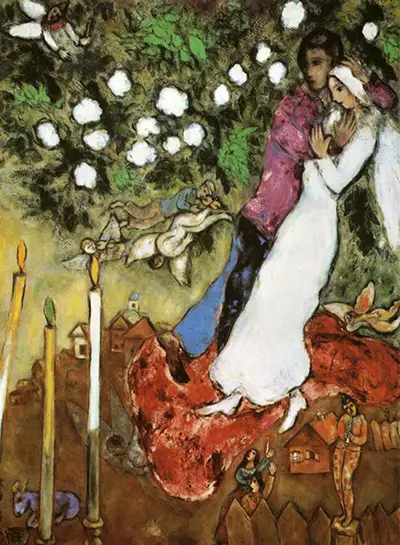

In The Three Candles, which he began in Paris in 1938, we see the motifs with particular clarity of a private memory and the strength of a wish.

The painting shows an embracing couple: the male figure’s arms are cradling and protecting, rather than caressing. They are set against, and perhaps partly sheltered by, a background of black and dark green foliage and a skein of white puffs of cloud-like blossom.

At the base of the tableau are more images that link to Chagall’s other work. There is the picket fence, although it is no longer contextualised in a conventional landscape, as in “Over Vitebsk”, but seems open and incomplete.

The clown musician is here, like one of the acrobats and merry-makers from Chagall’s epic tableau The Wedding Feast – but here he is a relegated and unsure figure, alone.

And the blue cow that has such symbolic, mood-setting presence in other works sits in the lower left-hand corner of the frame – not a powerful and mystical spirit, but a subdued and meek animal, beneath man.

While in Paris immediately before the First World War, Chagall was part of the same artistic circle as the poet Guillaume Apollinaire who, with Robert Delaunay, was briefly one of the proponents of Orphism.

This short-lived movement sought to focus on the aesthetic pleasure and sublime significance of art. While its commitment to abstract rather than figurative or narrative art would never win over Chagall, the theories of the Orphic artists around colour would have a more lasting influence.

In this work, with the clouds of a new conflict already gathering in the world outside, the palette suggests a growing unease, at least in Chagall’s private language of colour. The blue of freedom, dreams and striving emotion is hardly to be seen, compared with browns and black.

And below the woman’s feet, a dark angel unrolls a trail of red across the earth. Red in particular is to feature strongly in Chagall’s work in the years to come.

It is hard to read the winged figures of the painting as purely comforting or benign presences: they may be bringers of something, but something good or bad. Gliding, falling or drawing in the great wave of red across the painting, they remain an enigma.

In keeping with the rest of this compelling painting, the candles in the left foreground – and the green flame burning on one of them, and the empty candle holder alongside the three – defy any easy symbolical explanation.

The fourth candle is there, however, even if it is easy to miss at first: one of the two small figures at the base of the painting is holding a tiny, barely glowing light. The woman looks up to the embracing couple – a small element perhaps, but one that recalls votive or devotional art and the intensity of its meaning.